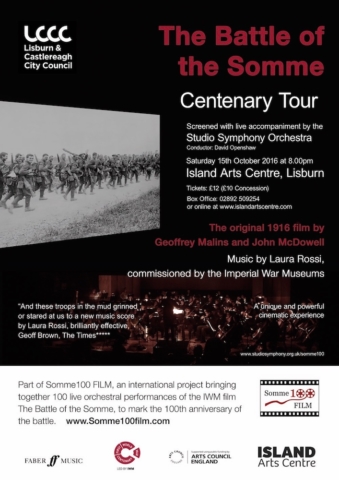

24 – Studio Symphony Orchestra conducted by David Openshaw

Date – 15th October 2016, 8:00 pm

Venue – Island Arts Centre, Lisburn, BT27 4RL

Pre Concert Talk

This talk was given by [waiting on name]

I’d like to give you a short introduction to the film you are about to see, and to put it in some historical context.

The Battle of the Somme was the first major offensive on the Western Front in which the British Army took the leading role. It was Britain’s contribution to a coordinated offensive with France, Italy and Russia across Europe to defeat the Germans after the setbacks of 1915. The first day of the battle on the 1st of July 1916 was the bloodiest in the history of the British Army. The campaign lasted for over four months, during which time the British and French suffered half a million casualties with a further half million casualties for the Germans.

The 36th Ulster Division was one of the few divisions to make significant gains on the first day. But this came at a heavy price with, in the first two days of fighting, 5,500 officers and enlisted men killed, wounded or missing. It was said of their division that “their attack was one of the finest displays of human courage in the world.” Of nine Victoria Crosses given to British forces on the first day of the battle, four were awarded to the 36th Division soldiers.

During September, in continuation of the same battle, the 16th Irish Division here and in other parts of France, also suffered horrendous casualties.

Towards the end of June 1916, two British official cinematographers, Geoffrey Malins and John McDowell, risked their lives by going to the front line to film the action, giving us an invaluable insight into the battle today. Filming took place over two weeks, covering the build-up and opening stages of the Battle of the Somme. The cameramen were attached to the 29th and the 7th divisions, so there is no footage of the Ulster or Irish Divisions.

The equipment used to film the battle consisted of large, hand-cranked cameras requiring a tripod for stability. The equipment was heavy, and the cameras could only be loaded with a few hundred feet of film at a time. It was also very difficult to film in poor light or at great distance.

Shot and screened in 1916, The Battle of the Somme was the first feature length documentary about war. The film was immensely popular and aroused great interest – by October 1916, just three months after the battle, the film was seen by around 20 million people in Britain and Ireland (the UK population at the time was 43 million).

The film is definitely a propaganda film, though it is shot and presented in the style of a documentary, and was made in response to a real desire from the British public for news of, and images from, the battlefront. It was created to rally civilian support, particularly for the production of munitions, and British soldiers are portrayed as well-fed, respectful to prisoners and well-looked after. A further purpose would have been to encourage British men to respond to their call-up papers, as many did not come forward after conscription was introduced; 93,000 men failed to appear at the recruiting office when called-up.

British and Irish audiences flocked to the cinemas in the hope of seeing someone they might know and to see what the fighting on the front was really like. Filmed as it was on the front line, it offered audiences a unique, almost tangible link to their family members on the battlefront.

Anticipating the desire of the audience to spot their loved ones, the cameramen captured as many faces as possible, often encouraging the men to turn and acknowledge the camera. Some scenes, such as the ‘over the top’ sequence, are now understood to have been staged. However, historians estimate that overall only 90 seconds of the film was shot in this way.

A small part of the film depicts images of wounded or dead soldiers and some distressing images of communal graves. The depiction of British dead is unique to this film in the history of British non-fiction cinema.

At the time, audience reactions to the film varied greatly; some members of the public thought the scenes of the dead were disrespectful or voyeuristic. There was debate in the newspapers and at least one cinema manager refused to show it. Some commentators pointed out that the film was as effective as anti-war propaganda as it was at meeting its intended purpose.

But most people believed it was their duty to see the film and experience the ‘reality’ of warfare. It’s popularity actually helped to raise the status of film itself from a trashy form of mass-entertainment to a more serious and poignant form of communication.

The Imperial War Museum took ownership of the film in 1920, and in 2002 undertook digital restoration of the surviving elements. The film is presented in five reels with short breaks in-between. It was, of course, made before the era of recorded sound on film, so there are written titles, provided by the War Office, to give commentary and point out important details.

In common with all cinema showings, the film was always screened with accompanying music. In 1916 it was accompanied by musicians playing a series of stirring patriotic tunes and marches. This jaunty and heroic music, whilst providing an insight into the way the film was first received, is less appropriate for today’s audiences.

So, in 2006, to mark the 90th anniversary of the battle, the Imperial War Museum commissioned composer Laura Rossi to write a special orchestral score as a soundtrack for the digitally restored film. The aim was to create music that would properly match the action on the screen and help contemporary audiences to better engage with the content.

To quote Laura:

“It was very challenging writing the music because the film has some really abrupt changes of mood – for example the scene showing happy soldiers receiving their mail suddenly cuts to a view of dead bodies in a crater – so it was hard to achieve the right tone and to make the music flow between such contrasting scenes.

I wanted to deal with some of the more shocking or distressing scenes in a sensitive way, not loading them with over-romantic or tragic music but providing something simple to give the viewer the space to think about what they are seeing on the screen. I did not want the music to be too emotional or tell the audience what to feel. The images are powerful enough themselves.”

The Battle of the Somme is the jewel in the crown of the Imperial War Museum’s collection.

It is a compelling documentary record of one of the key battles of the First World War and the first feature-length documentary film record of combat. Seen by many millions of British civilians within the first month of distribution, The Battle of the Somme was recognized at the time as a phenomenon. It allowed the civilian home‐front audience to share the experiences of the front‐line soldier and was seen by mass audiences in allied and neutral countries, including Russia and the United States.

It remains one of the most successful films ever made. It was not beaten in box office records until Star Wars in 1977.

The film is the source of many iconic images from the First World War, which remain in almost daily use a hundred years later. If you have seen any documentary about World War 1, it is likely you have seen part of the film.

The tragic events at the Battle of the Somme left a deep mark on a huge scale. Nearly everyone in the UK will have an ancestor who fought or died at the Somme.

In this centenary year, the Studio Symphony Orchestra is proud to be presenting the only screening of the film with live accompaniment in Northern Ireland. We hope you will find it a rewarding experience.